A Robust Bond

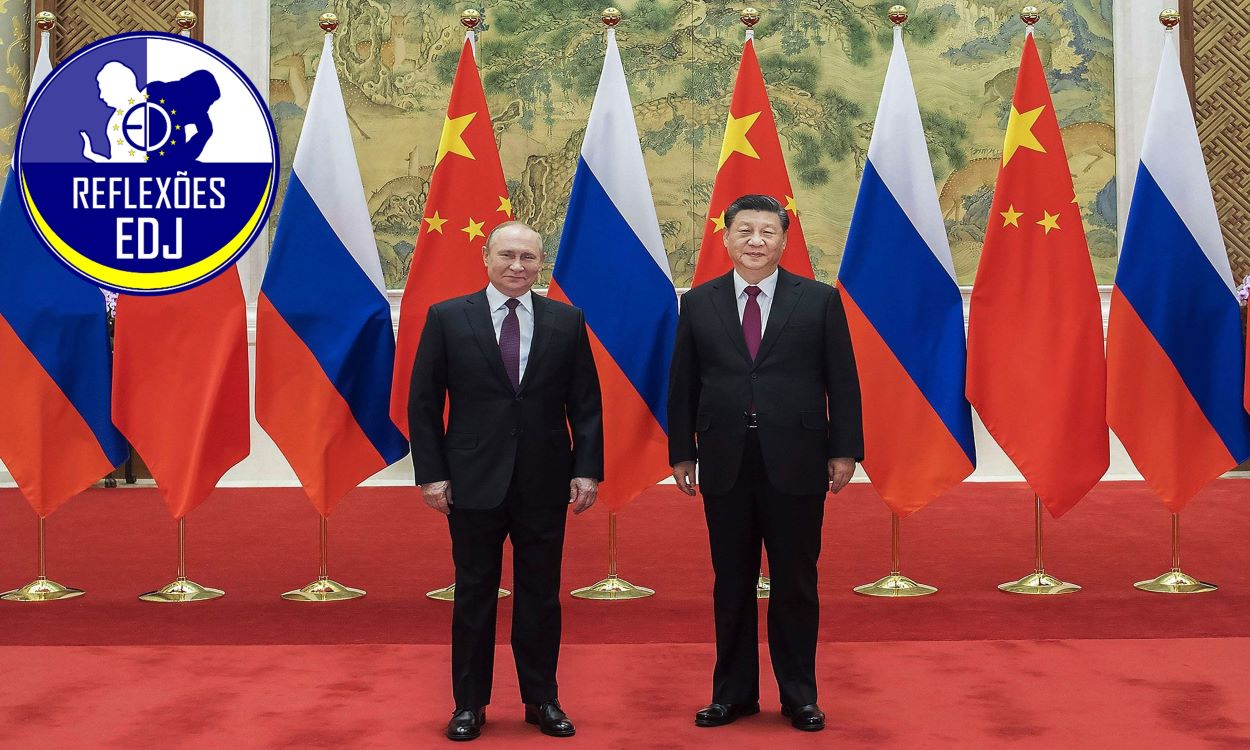

The day is February 4th, 2022. The location is the Beijing National Stadium, and the occasion is the opening ceremony of the Winter Olympic Games where Presidents Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin would meet once again. A subsequent joint statement would label China and Russia’s bilateral partnership as one with ‘no limits’. The statement indicates an upgrade to relations when compared to the 2019 statement of similar nature that dubbed the link as a “comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination for a new era”. (Kim, 2023)

Invoking a ‘new era’ while tagging each other as strategic partners for its coordination had confirmed at the time the aligned revisionist sentiment of both countries, raising the questions as to how far are the willing to support each other, how feasible is the signing of a treaty for a military alliance and how sustainable may such a relationship be.

Ever since the ‘new era’ declaration of intent, military ties have grown to the point of them becoming each other’s “most important foreign exercise partner” (Weitz,2021), while the flux of bilateral economic trade has followed suit, with operation even being increasingly transacted in local currencies. On paper, the Sino-Russian relationship may look healthy and mutually beneficial over the long-term aspect of affairs.

The Continuous Third Party of the relationship

Let us take a moment to visit the city of Harbin in the Heilongjiang Province in the north of China. As one reaches the city, its cold weather and heavily Russian architecture become strikingly interesting aspects. As Imperial Russia would build a railway throughout the region, the city would grow out of a small village at the end of the 19th century – it was indeed Russian territory at the time. Nowadays there lies an old Russian Orthodox Cathedral which has been turned into a tourist site by Chinese authorities. It is also a symbol of how sanitized the violent past between both countries has become, even though it has not been forgotten. (The Economist, 2023)

Beyond the bloody border conflict that partly took place in the Province at hand, the Sino-Soviet split was highly ideological, even regarding how to perpetuate the internationalization of communist ideals in practical terms. But the fundamental aspect of discord is of geopolitical nature due to competing visions on how to deal with the West. As explained by Joseph Torigian via The Economist (2023):

“In the 1950’s and 1960’s the Soviet Union certainly wanted to compete with the United States, but Nikita Krutchev was also worried about competition going off the rails and he was afraid of nuclear war in particular. China, on the other hand, felt like it was left out of the international system, and they wanted a more aggressive position towards the West in support for revolutions throughout the world.”

This serves as an example as to how the significance of the West cannot be understated regarding the genesis of current day Sino-Russian alignment. Nowadays, the long-term objective of reaching a ‘new era’ results from common terms in geopolitical interests:

- Both seek a multipolar world with a more even distribution of power;

- Both have an antagonistic attitude towards the West due to a…;

- … Grudge to American hegemony;

- And above all, both countries want a greater say in global affairs, as their histories demonstrate how deserving they are of such influence. They consider themselves civilizational states and thus shape their domestic and foreign policies accordingly.

Having accused Washington of making the most of the Dollar’s economic influence as a vehicle with which to establish the primacy of western values and to impose punitive measures on its rivals, there has risen a deep ideological alignment with the United States at its core, with the main objective of weakening U.S-led alliance architectures in both Europe and Asia. Measures such as the commitment to deepen ties in various ways; the pushing for international transactions to not be performed via Dollar but by Rubles and Renminbi; and of course, the advancement of the narrative that Western countries have violated the principle of ‘indivisible security’, justifying the war in Ukraine; among others, all fit the objective at hand. (Kim, 2023)

In order to understand the Sino-Russian alignment of today it is paramount for one to consider the relationship as a triangular one.

History Doesn’t Repeat but It Rhymes

Going back to Harbin and the question as to how feasible the signing of a military treaty between both parties is, the history of the border disputes will illustrate another major factor of this relationship as both countries showcase striking disparities.

From the war effort to the difference in defense expenditure and technological development over the last years make it expected that the Chinese military surpasses that of Russia’s. Meanwhile, trade and GDP disparities suggest that the bilateral relationship has grown more important to Russia than for the Red Giant. Combining such military and economic disparities, a binding treaty would surely place China as the senior partner – a condition too slippery even for a gambler as Putin to risk slipping into, thus aiming for a multipolar order.

Demographic disparities must also be considered as the Russian Far East remains vastly underpopulated in comparison to the more populous and prosperous Chinese border area. As both countries have invoked historic narratives to support geopolitical ambitions (Ukraine and the South China Sea for example), it is important that the Chinese understand that the Russian Far East, including the strategic port city of Vladivostok was forcibly seized from China in the mid-19th century. There is the risk that future policy narratives are incompatible and inflammatory and, as the junior partner, concessions may be forced out of Russia with regards to this possible flashpoint. (Caspian Report, 2021)

Adding to it, competition in Central Asia must also be accounted for as Russia retains the leadership legacy of the Soviet Union, while major (long term) projects such as the BRI signify a threat to such status by definition.

All disparities combined make it so that there is no real fertile ground to establish a binding treaty that would lead to a long term alliance – a relationship of strategic convenience with the West as the major unifying factor.

On top of boasting a more economic and robust economy and higher technological capabilities the War in Ukraine has exacerbated the geopolitical disparity between the two. As Russia has been cut from most of the Western world, China has become its major pillar for diplomatic and economic support. It has enveloped most of Russia’s overall trade and it has become an essential market for Russian exports while consumers are still more likely to rely on Chinese goods – possibly a window of opportunity for the Renminbi to be asserted as a strong regional and international currency. (Gabuev, 2022)

However, one hand will wash the other as the degree of interdependence between both countries is still quite high despite the clear asymmetry. Despite economic interdependence with the West, China would still sit on the fence regarding the Russo-Ukrainian conflict, Crimea 2014 included.

The two share a 4200 Kilometer border and the content of their economic relationship is quite complementary as Russia is rich in natural resources but lacks significant technology and investments, while China can provide exactly that amid craving for natural resources to keep fueling its industrial sector. Beyond that, the sophisticated weaponry from Russian factories is well received. As China’s share percentage of Russian trade keeps growing it gains more control of areas of technological importance such as transport, energy production and communications, holding grat geopolitical leverage. (Gabuev, 2022)

These are major incentives for China to provide a lifeline for Russia beyond the near future and sustain a friendly regime in Moscow (which helps explain the Chinese position regarding Ukraine).

So, What Lies Ahead?

To recap, the Sino-Russian relationship, like many other interstate relationships, demonstrates both opportunities and potential threats to both parties.

Due to the European security context, the continent is no longer the main recipient of Russian exports, resulting in the primacy of the Chinese market in the disposal of its product. In other words, Russia assists China in meeting important economic and energy needs. Such a situation has been well received in Beijing in view of the consequent decrease in prices, motivating the maintenance of a strong commercial relationship between both parties.

However, economic ties contribute to China walking a fine line on the international stage. The context of the invasion of Ukraine carry with them an element of risk due to the possibility of economic sanctions being applied by Western entities. While China demonstrates a stance based on not criticizing the invasion and providing Russia with a diplomatic and economic lifeline, it has also acted in accordance with the sanctions applied to the Federation.

It is important to note that interrelated pivotal points in the international orientation of both China and Russia, such as the rejection of Western dominance on the international stage and the (consequent) preference for a multipolar order based on a more balanced distribution of power and influence among the major powers, contribute to this being a relationship endowed with its strategic convenience.

So where do we go from here?

This is a relationship of complex analysis, especially when including the “time” factor for both opportunities and threats to both states. Other opportunities and threats could have been highlighted such as the potential for Russia to serve as an entry point to China in matters relating to the increasing melting ice in the Arctic; the possibility of a coordination of actions that can serve the interests of both in the Central Asian region where both powers have been enjoying a great deal of leverage; or the strong mutual diplomatic support within the United Nations Security Council. However, while these points can be intuitively seen as opportunities, the Sino-Russian relationship is also strongly characterized by the strong ties between its leaders Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping, in addition to the previously mentioned focal points. In the long run with the perceived decline of the West or a post-Putin Russia, there would be many open questions in the relationship.

The opportunities and threats highlighted and discussed are certainly worthy of such treatment, but the real point of uncertainty lies in the unpredictability of Russia’s future, as this is an unavoidable factor in the long term.

Chinese power depends on a state architecture that puts into practice the decisions made by the Chinese Communist Party. In practical terms, it is who governs most from the National Congress to the General Secretary, meaning that Xi Jinping is at the center of the decision-making process. Still, the present structure allows a hierarchy to be obeyed at critical moments.

In contrast, the structure and stability of Russian power is based on Putin’s trust in what has consequently become his elite. The distribution of such power is done in a highly personalized way starting from the President to his closest circle so that he maintains his control.

Although both are authoritarian and personalized systems, the Russian system lacks a foundation for long-term stability. Thus, the future of Russia in a post-Putin perspective, like the stability of the relationship in question, will depend heavily on what will or will not be the preparations for the end of his real power. Between threats and opportunities, circumstances will be determinant in their designations.

What has assured stable coordination between both countries have been their main protagonists Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin and the fact they see eye-to-eye in fundamental aspects of international politics. Regardless of how long it may take, their time in power will remain limited as all things naturally come to an end. Beyond disparities that may lead to future flashpoints between China and Russia, this is a determining factor over the long term. One for which no one has a real answer to yet on the Russian side of things.

The Putin elite equates to a social network of unfathomable domestic power with the President at its center. By shielding himself and his power with rings of trust, he has managed to govern the Russian Federation at his will. Even Though such a system has brought the country some much needed stability and economic resurgence after the Yeltsin years, it is a system with no clear stability assurances for the following generations. A post-Putin Russia is not as far-fetched as it once was and it is a scenario that must be accounted for as it will yield unpredictable results.

The escalation of violence in Ukraine has drawn the major lines of Russia’s future under the rule of its current President. There is no going back on that. And while there are major factors in favor of China coming out as a major winner, there is also a huge question left to be answered amidst Sino-Russian relations which is, “where will we go from here?”. The problem is that not even the Russian people and elite are ready to provide significant commentary on.

02 de maio de 2023

Emmanuel Carneiro

EuroDefense Jovem Portugal

Notes

Caspian Report. (2021, January 8). Unpacking the china-russia alliance. YouTube. Retrieved May 1, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AGafVj-wrmw&t=655s

The Economist. (2023, February 7). Drum tower: Waiting games. Spotify. Retrieved May 1, 2023, from https://open.spotify.com/episode/3Jb9PEuKf1d7uXbx9K55ce

Gabuev, A. (2023, April 19). China’s new vassal. Foreign Affairs. Retrieved May 1, 2023, from https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/chinas-new-vassal

Kim, P. M. (2023, April 18). The limits of the no-limits partnership. Foreign Affairs. Retrieved May 1, 2023, from https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/limits-of-a-no-limits-partnership-china-russia

Weitz, R. (2021, July 9). Assessing Chinese-russian military exercises: Past Progress and Future Trends. CSIS. Retrieved May 1, 2023, from https://www.csis.org/analysis/assessing-chinese-russian-military-exercises-past-progress-and-future-trends

NOTA:

- As opiniões livremente expressas nas publicações da EuroDefense-Portugal vinculam apenas os seus autores, não podendo ser vistas como refletindo uma posição oficial do Centro de Estudos EuroDefense-Portugal.

- Os elementos de audiovisual são meramente ilustrativos, podendo não existir ligação direta com o texto.