On September 11th of 2001, nineteen al-Qaeda members hijacked four American commercial planes: two crashed against the Twin Towers in New York City; a third in the Pentagon area (Washington D.C) and the fourth in Pennsylvania. In this day, often known as 9/11, nearly three thousand people were killed and six thousand were injured. The 9/11 Commission Report, the “official government edition” of the events, argues that it “was a day of unprecedented shock and suffering in the history of the United States” (U.S). Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the mastermind of the attacks according to the Report – detained at Guantánamo Bay prison since 2006 and whose pre-trial hearing will be held in November 2023 -, has changed how the world perceive terrorism and security.

Indeed, the attack had a global impact: although several challenge this idea, security analysts tend to consider 9/11 to be a major game-changer to international security, especially in the field of counterterrorism, or on how states decide to respond to terrorism. After 9/11, national states and multilateral organisations – from the United Nations to the European Union – adopted new legislative measures to respond to what security services perceived as a “new threat”. It was the beginning of a “new world”, the “war on terror” doctrine, leading to the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, and a greater emphasis on military instruments to combat terrorism.

In 2023, twenty-two years after “the most lethal act of non-state terrorism act”, are we safer from terrorist attacks? There are multiple ways to address this vast question: this text briefly debates some hypothesis, taking into account the phenomenon of transnational terrorism, while looking at the European Union context. As argued elsewhere, here we define terrorism as violence perpetrated by non-state actors against a state, in order to achieve political aims. We begin with a brief analysis of the evolution of the terrorist threat.

1. THE TERRORIST THREAT

Accessing the evolution of the terrorist threat since 9/11 surpasses the scope of this text. It is suffice to highlight some trends at the global and regional (European Union) levels. The analysis is conducted through three dimensions:

1. Root causes: There is no consensus about the root causes. Terrorism is correlated to a range of factors, from psychological to social. Nonetheless, according to the Global Terrorism Index (GTI) (2020), “conflict has been globally the primary driver of terrorism since 2002”, a conclusion also reinforced by the UN (2020). In the European Union – or in western / high-income societies / OECE countries – the main root causes are broadly associated with the lack of socio-economic opportunities, corruption, the feelings of social alienation and state involvement in foreign conflicts.

2. Type of terrorism / deaths: Most terrorist attacks around the world are perpetrated by ethno-nationalist/separatist groups. Looking at Europol’s data, the European Union follows the same pattern, although jihadist terrorism is responsible for the majority of deaths within this region. International reports also highlight the rise of right-wing groups as a major trend, which can further enhance violent extremism and terrorist activities, based on xenophobic and anti-Semitic rhetoric.

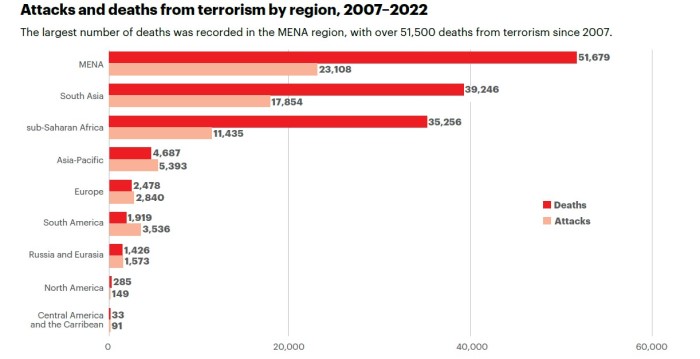

3. Geography of the attacks: According to the GPI (2020) globally, “after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, most terrorist activity was concentrated in Iraq and Afghanistan for nearly a decade”. The most recent GPI report (2023) states that “the epicentre of terrorism has shifted from the Middle East and North Africa into sub-Saharan Africa, especially the Sahel”. Nonetheless, considering data between 2007 and 2022, the MENA region still accounts for the biggest number of attacks and deaths. Europe remains the most peaceful region in world. However, the terrorist threat persists: there are growing security concerns about the return of foreign terrorist fighters to European soil, lone actors and the rise of right-wing extremism.

2. ARE WE SAFER?

Yes, we are safer. Proponents argue that, regardless of the geographical area, we are generally safer from terrorist attacks because of the legislation adopted since 9/11, at the national, regional and international level. This, therefore, includes the measures taken by the national states and major international organisations such as the United Nations, European Union, Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), North Atlantic Organization (NATO) or the Council of Europe. From the International Relations standpoint, this would be the typical reasoning of Liberals: in order to be secure, states emphasise that multilateral responses, collective security and international cooperation are the fundamental keys to address any kind of transnational threats. From this point of view, fighting against terrorism should focus in criminal measures, while ensuring respect for human rights.

No, we are not safer. Critics might point out two arguments. First, despite legislation reinforcements along the years, safety is not a question of implementing more legislation but of its efficacy. Accessing the efficacy of counterterrorism measures is still a very difficult process. Terrorism, they argue, is one of the major threats to peace and security, along with other transnational threats like climate change or cyberattacks. Second, most experts and analysts recognise that no society is immune to the terrorist threat (regardless of its ideology) and it will survive as long as terrorists consider it to be a valid strategic option to achieve their political aims. Therefore, taking into account a broad Realist standpoint, safety/security is always uncertain, but if you want to be safe you should seek power and choose a military approach.

Safer? It Depends. In reality, the answer is much more complex than the yes-no binary argument. In my view, legislation did make the world safer, yet the risk is still very distinct between and intra geographical contexts. For instance, the situation in Europe is different from the Middle East, and so forth. In fact, being “safer” is about “politics” as much it is about “security”. It is political because it depends on how terrorists perceive violence to achieve their goals, and on how states perceive the threat. It is about security because it deals with direct victims and potential great disruption in multiple areas that need effective protection. This means implementing policies and programmes aimed at countering different aspects of the threat, such as root causes; radicalisation of individuals; financing of terrorism groups; and preventing critical infrastructures and citizens.

Ultimately, as disappointing this might sound, we are safer as much we are not. According to Jonathan Evans, former Director General of MI5 (2007-2013), “risk can be managed and reduced but it cannot be realistically be abolished”. So, in fact, as Professor Richard English says, “the main problem is not terrorism but how we respond” – and this is the key variable that determines whether we are / will be safer or not. The best responses, in my view, are a hybrid set of criminal and military measures, while stressing the need to ensure human rights and tackle violent extremism as fundamental priorities.

19 de setembro de 2023

Joana Araújo Lopes é Doutoranda em “História, Estudos de Segurança e Defesa” no ISCTE. É bolseira da FCT e trabalha numa tese sobre o contraterrorismo em Portugal e Espanha, no contexto da União Europeia (2004-2020). É Mestre em Ciência Política e Relações Internacionais pela Universidade NOVA de Lisboa (2017). Trabalhou como estagiária na Embaixada Americana em Lisboa (Assuntos Consulares), no Ministério dos Negócios Estrangeiros (MNE) (Direção-Geral de Política Externa) e no Instituto da Defesa Nacional (IDN). Os seus principais interesses de investigação incidem sobre a segurança internacional, o terrorismo, o contraterrorismo, a radicalização, o extremismo violento e a diplomacia.