Introduction

In the last 20 years, we have witnessed a conjectural change of power in the international system, where, nowadays, we witness a greater quest for power not only by one actor, but by several. The world as we know is in constant change, not only in the political panorama, but also in the economic and above all, in the technological panorama, whose changes profoundly influence the “hierarchy” of the international system.

One of the regions that has gained more value and, at the same time, has remained somewhat out of the international media spotlight (for deliberate reasons or simply because something of greater relevance is happening) has been the Arctic area, which has been the target of increasing interest by the world’s major powers, both for the resources that the region holds and that may have the ability to change the world energy game, and as a means to influence other actors in the international scene

One of these interested powers is China, a country that is not in the Arctic Council because it does not have sovereignty over any area of the region, but that sees in the Arctic an opportunity to consolidate its influence around the globe, either from the energy resources it can obtain, or in the improvement of its trade routes, or in the exertion of influence from projects such as the “Polar Silk Road”, which will be addressed in this reflection.

This reflection aims to make us understand what Beijing’s interests are in the region, why they exist and how they can be materialized. It also aims to show what the western response has been and how effective China has been in its plans.

What is the Arctic Council?

In order to begin to explain how China can materialize its interests in the region, is important to know one of the most relevant actors that determines a lot of the policies that are applied in the Arctic. This organization is called “The Arctic Council”.

The Arctic Council is considered to be a high-level intergovernmental organization that addresses issues faced by the Arctic governments. It was established in 1996 through the Ottawa Declaration, which all of its current members signed. The council counts as its members the States that possess sovereignty over lands within the Arctic and only those who meet this requirement can be members of it, with those being: The United States; Canada; Russia; the Kingdom of Denmark; Sweden; Iceland; Norway; and Finland. (Artic Council, s.d.)

Recently, the Council has drawn the its strategic plan for 2021-2030, where they set the strategic goals for the organization, with those being related to sustainable development in areas of economy, the environment and society. Although they don´t mention the importance of other actors than the ones that pretence to the Council, they do mention that they want to “enhance constructive, balanced, and meaningful Observer engagement and encourage their proactive engagement in relevant activities of the Council”. (Artic Council, 2021) Which is relevant to China, since the country has an Observer status on the Council.

Why does China want to get into the Arctic Council?

It’s not clear that China wants to get into the Arctic Council specifically, since as said before, the only countries that are eligible to be members of it are countries that possess sovereignty over lands within the Arctic. That doesn’t mean China doesn’t want to play a bigger role in the region. In fact, the former self called “Middle Kingdom” already is somewhat of a constituent of the organization. As stated before, the country has a status of “Observer”, which means that they can attend the meetings of the council, observe its work and purpose projects through an Arctic State, with the objection that the financial contribution for it cannot exceed the financing from Arctic States.

The Asian superpower, as stated by its government in 2018 in a document called “China’s Arctic Policy”, sees itself as “a near arctic-state” (People´s Republic of China, 2018) and one of the continental states that are closer to the Arctic Circle. They also see themselves as an important stakeholder since the natural conditions of the region and their possible changes directly affect the country’s climate system and environment and subsequently its agriculture, fishery and economy.

The way China pretends to exert its influence is similar to how China has been behaving in other regions of the globe. With the implementation of investment projects in other countries. Similar to the “Belt and Road Initiative, in 2018 it was introduced the “Polar Silk Road” (PSR), a project that aims to connect three major economic centres, North America, East Asia, and Western Europe, via the Arctic Circle.

By reading the document with China’s Arctic Policy, we can split their strategy and reasons for why such interest in the region in 3 parts:

- The natural resources of the Arctic;

- The commercial routes;

- A way to enhance China´s international image with the PSR and how is it going nowadays

The natural resources of the Arctic

The Arctic is home for a lot of valuable energy and raw material resources that aren´t excavated as of today due to its tough extraction. It is known that the region holds around 13% of the world’s undiscovered crude oil and around 30% of undiscovered natural gas. (Nakano, 2018) Although, as said before, to reach these resources is difficult, since they are locked away under the Arctic, but we´ve seen some progress due to the retreat of the sea ice that has made extraction viable in some areas.

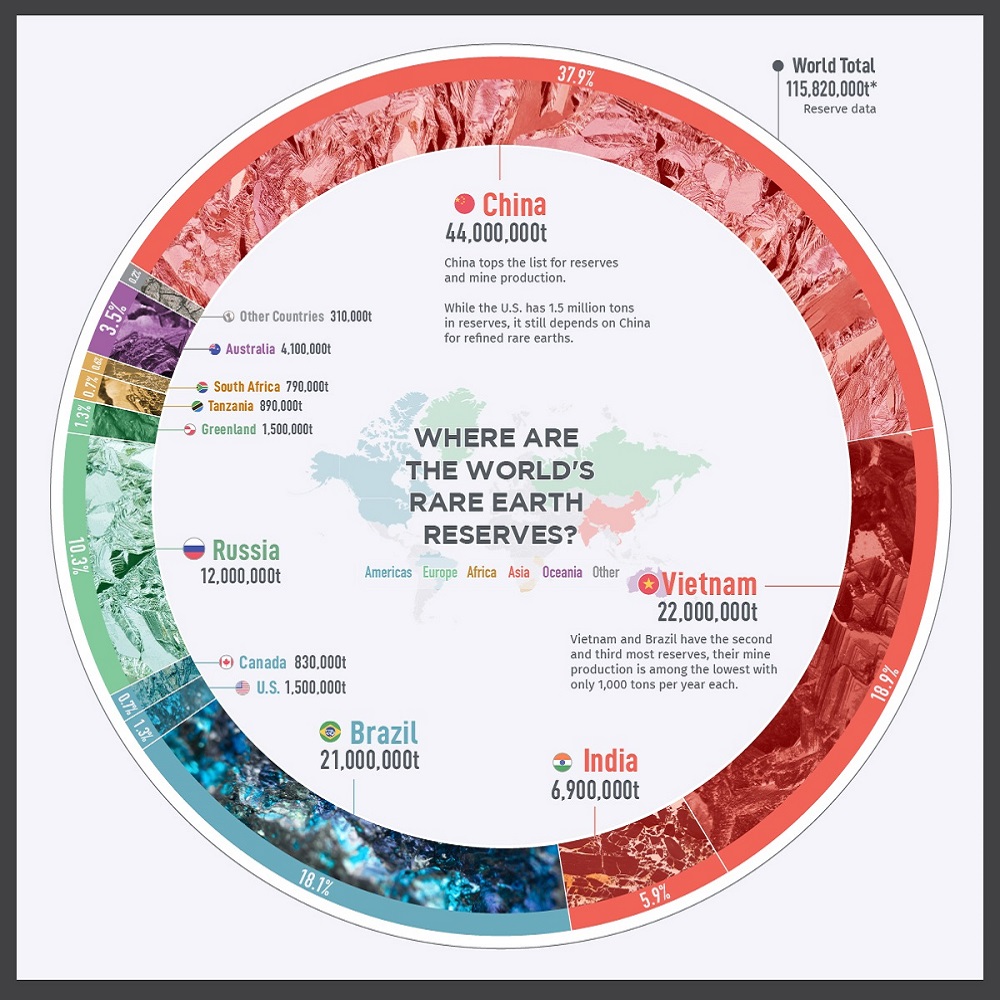

Another factor, and maybe even more relevant than the presence of oil and natural gas in the region, may be the fact that it possesses about a quarter of the world´s rare earth elements (REE). With names such as cerium and lanthanum, rare earths elements contain key ingredients used in many of today’s technologies, from smartphones to electric cars, as well as military tools. This is important not only because the materials have an enormous value in today´s economy, but also because China is one of the world’s countries who have the most amount of it. In fact, if we take a close look at where these materials exist the most, we can note that the countries that hold a higher percentage of them are part of an association known as BRICS, which unites 5 of the world´s major emerging economies (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa).

Source: Visual Capitalist

China’s strategy to extract these minerals follows the thought of keeping the competition away from some sort of independence from them. This can be seen through the urge of the Trump Administration to get them, declaring that getting the REE was essential to guarantee “national defence” of the country. Also speaking putting in consideration purchasing Greenland from Denmark, which if happened, would give the US independence from importations of these materials from competitors.

Commercial routes

There are two paths through the Arctic that may serve as better and more efficient alternatives than the ones currently used for shipping expediency methods. The Northwest Passage (NWP) and Northeast Passage (NEP) mean a faster way to get North American and European energy goods to China (Nakano, 2018). Shipping through the Northern Sea Route in general would shave almost 20 days off the regular time using the traditional route through the Suez Canal, according to Reuters. However, with the exception of the North Sea Route portion of the Northeast Passage, the majority of the Arctic routes have poor infrastructure and search and rescue capabilities. Other barriers, such as increased insurance premiums and variable seasonal conditions may deter increased volumes of trade through these routes until decades later.

The NEP provides an alternative trade lane through North Sea Route waters within Russia’s Exclusive Economic Zone that circumvents the maritime choke point at the Strait of Malacca, as well as pirate-infested waters, such as the Red Sea and Indian Ocean. Such security risk is marked poignantly by the pirate attack on Chinese-owned COSCO Asia in the Suez Canal in 2013, while its sister ship, the Yong Shen neared the end of its voyage to become the first Chinese cargo ship to transit the NEP. Thus, China´s interest in the Northeast Passage would be materialized in reformulating the infrastructure needed to support the passage of cargo through that area. Which could be done with the other façade of the “Polar Silk Road “plan, by investing in the Arctic countries in the same way as the “Belt and Road Initiative” has done.

A way to enhance China´s international image with the PSR and how is it going nowadays

If we take consideration of what´s at stake, China may see in the Arctic a good opportunity to strengthen its geopolitical and geo-economics posture in the international scene. As said by Jane Nakano on CSIS: “Potential shipping routes through Arctic waters would offer Chinese vessels the ability to circumvent the widely used paths to China from Europe that pass through the Suez Canal or around the Cape of Good Hope where the U.S. Navy has long been dominant.”. (Nakano, 2018)

In some sense, we can see the Polar Silk Road, which includes the expansion of local economic partnerships, infrastructure development, extractive industries, and emerging maritime shipping corridors as a way to enhance its image as a major global power (Tiburzi, 2022). However, in recent times, its impact on the region has been substantially less than anticipated, with the Russian invasion of Ukraine pushing the Chinese Arctic policy slightly backwards. Many initial components of the PSR across the Arctic Ocean have been postponed or abandoned outright, either due to shifting political priorities or particular concerns expressed by Arctic nations about the financial and security dangers of Chinese investments (Lanteigne, 2022).

At the same time, the PSR has also been affected by the “halt” in the Arctic Council since March owing to the Ukraine crisis. Since China is a formal “observer” in that organization, they cannot vote but can participate in Council actions. The Arctic Council has been a critical platform for Beijing to demonstrate its desire in being a partner for Arctic governments, and the question now is how China’s polar interests would be harmed if the Council stays split in the long run. The Polar Silk Road was based on the assumption that the Arctic governments would retain a certain amount of cooperation, allowing Chinese companies to operate freely. This was undoubtedly true when the Arctic Council was established in the late 1990s, but the Council was put under strain following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, before eventually collapsing this year (Lanteigne, 2022).

Western Response

The West response, mainly represented by the United States, has been until recently, had a quiet response, this until 2019, when the Secretary of State Mike Pompeo criticised China for their actions in the Arctic.

The American superpower’s reaction can be seen from several perspectives, one of them at the military level. At the 2018 NATO Summit, it had been confirmed that the US 2nd Fleet will have a special focus on securing US interests in the North Atlantic and Arctic waters. Something that has been able to be seen through the first military exercises in the region for decades.

Seen from another perspective, the USA also seeks to exert its influence through countries with which it has closer ties. An example of this is the relationship between the Americans and Denmark, which refused help from China to restore some ports and airports and also to buy a port through a Chinese company. The strange factor in this refusal is that China is one of the biggest commercial partners Denmark has, but they don’t allow the Asian´s country to act in Greenland, a semi-autonomous country under the kingdom of Denmark and where the US has a lot of their interests. This interest surges with the expectancy that an access to Greenland’s resources could help break U.S. dependency on China for rare earths elements. Allied with this thought, a meeting with the Prime Minister of Canada Justin Trudeau and NATO´s Secretary- General Jens Stoltenberg seemed to be critic and alert to the Polar Silk Road strategy, highlighting that China has been “investing tens of billions of dollars in energy, infrastructure, and research projects in the High North”, seeing it as a challenge for the security in the region.

Conclusion

The world seems to now understand the value that the Artic possesses for the future, making the region a huge competition between superpowers. Natural resources that may mean a shift in the order of power in technology markets, along with improvements in forms of freight transport that could help to increasingly interconnect the globe are the main “material” reasons behind why one would have such interest in the Artic. But behind these reasons also lies a quest for power and influence across the globe by all involved, not just China. In fact, China is only one of the 13 countries that have the “observer” status on the Arctic Council, of which 5 are Asian, and with China being one of the world´s most powerful economies, it makes sense for them to want to have a word about what happens around the globe. But the challenges that Beijing is presently encountering in building their strategies highlight the reality that the nation is still far from being able to unilaterally upend Arctic governance and is heavily reliant on Arctic countries and organizations to achieve its interests there.

However, China will not renounce its Arctic ambitions and still regards the far north as a “new strategic frontier.” As a result, it may be premature to see their main project, the Polar Silk Road, as a strategy that could have been getting better results. Nonetheless, it is critical for Arctic nations to take note of the PSR’s unsteady trajectory since its beginning in order to better comprehend Beijing’s ambitions and constraints in the Arctic as they genuinely are.

25 de outubro de 2022

Tomás Duarte Ferreira

EuroDefense Jovem Portugal

Bibliography

Artic Council. (2021). Arctic Council Strategic Plan 2021 to 2030.

Artic Council. (n.d.). https://www.arctic-council.org/about/timeline/.

Lanteigne, M. (2022). The Rise (and Fall?) of the Polar Silk Road. The Diplomat . – https://thediplomat.com/2022/08/the-rise-and-fall-of-the-polar-silk-road/

Nakano, J. (2018). China Launches the Polar Silk Road. CSIS. – https://www.csis.org/analysis/china-launches-polar-silk-road

People´s Republic of China. (2018). China’s Arctic Policy. – https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2018/01/26/content_281476026660336.htm

Tiburzi, F. (2022). China’s Polar Silk Road and geopolitics of the Arctic zone. Em Geopolitical Report .

Silk Road Briefing (2021) New Polar Silk Roads Discussed At The Arctic Circle Assembly.

Reuters. (2018). China unveils vision for ‘Polar Silk Road’ across Arctic

NOTA:

- As opiniões livremente expressas nas publicações da EuroDefense-Portugal vinculam apenas os seus autores, não podendo ser vistas como refletindo uma posição oficial do Centro de Estudos EuroDefense-Portugal.

- Os elementos de audiovisual são meramente ilustrativos, podendo não existir ligação direta com o texto.